Writing into the Storm

How do you keep writing when big chunks of the world keep falling on your head? How often have we all said “If only all this would stop, just for a minute, and let me get my feet under myself!”

But it’s not going to stop. You and I know that. Things we thought were solid and real and reliable are crumbling all around us, social agreements which took decades to build are being shredded as fast as the glaciers are melting—a tragic waste of courage and leadership which might never come again.

How does one write fiction in times like these? What should it even look like? How do we even calm down enough to write when the world is on fire? Funny enough, I recently finished a novel set during the Russian Revolution—so I’ve been living through intense social changes imaginatively for the last decade. But only now am I experiencing a taste of it for myself.

I think our first problem comes when we think things should be different than they are. Of course they should be. But they aren’t. They are this ugly mess. Sure, I am doing my fair share of political observation and screed-writing, yowling and spitting, holding up my signs, posting on the interwebs. I do what I can to make things better.

But I’m a writer of fiction. As such, I’m going to say there’s a certain value in accepting that this is the way it is right now. This is our crumbling world, coming apart at the seams, run into the ground by evil, greedy men for the purposes of the very few. My fiction writer self needs to accept that this is who we are, what it is, if I’m going to do the work that I was put on this earth to do.

This is now. This is real, this is us. This is the cage we’re in.

What’s a fiction writer to do with a world she doesn’t recognize, when change is coming at her so fast it’s a blur of painful objects hurtling past? Does she give it all up and turn to political commentary?

From what I can see, there are enough pundits and political writers handling that job, and doing it better than I ever could. I feel no need to pile on with my own off-the cuff commentary. But I can do something they can’t. I feel, I experience, and then I couch those feelings in made up stories which resonate with other human beings, one at a time, validating their experience, and raising questions about the nature of the human condition.

To do my work, I have to honor the feelings that come up. Not just rage, but all the other ragged feelings that beset me every day. Vulnerability, fragility, dread. Aversion and paranoia. Apocalyptic thoughts. Terror. I need to experience them and then somehow pull these emotions through this quivering organism I call myself--and weave them into some kind of form, called art.

It’s a paradox. Because as a person--as an American, as a Californian of a certain generation--I want to feel happy. Not just ‘okay’ but blissfully happy. Yippee Skippy. I want to be hopeful. I want to find silver linings. I want to bound out of bed in the morning, eager for the day as a Golden Retriever. I not only want to feel better, I want to make YOU feel better. I want to believe all this will turn out OK. I want to reassure you it will.

When what I actually feel is—sick, disgusted, frightened, apocalyptic, enraged, a near-constant state of dread and grief. Most of all, I want to get rid of these sick awful feelings. I want to talk myself out of them, I want to journal and meditate them away. I take refuge in exchanging clever mordant posts on social media with other people doing the same, making fun of what I fear most.

As an artist, however, the most important thing is for me to honor these feelings, not to run from them, or repress them, but to accept them and value them, in all their heat and and shameful weakness, and pull them through into my art.

It’s the key to writing fiction in times like these. To allow yourself experience the prismatic quality of these big emotions, accept them as where we’re at, and find a form to hold them.

Did you think I was going to give you tips to feel better?

The only thing that makes a writer feel better is to not sit with those feelings but to pull them through. To use them, to make something with them.

We need to be able to acknowledge these painful feelings which most people prefer to avoid—vulnerability, weakness, exhaustion, confusion, dread, guilt, shame. Humans like to armor themselves against these weak feelings and substitute less vulnerable emotions like anger or irony. As we have seen so often, anger feels powerful. We live in an angry society because people are unwilling to feel their helplessness, their vulnerability, their brokenness and isolation.

But it’s the weak and painful feelings which resonate most, these intimate feelings that are us at our most human. The artist must carry the emotions which most people find too painful or precarious to acknowledge, let alone value. This is what it means to be an artist. The artist is, to a certain degree, society’s sacrifice. You willingly take on the burden of the most intense feeling, like a lightning rod, in order to share it with others, to put it in a form that others, so busy repressing and deflecting, might be willing to take in. The beauty we create is the lure which allows people to experience these darker sides of the human condition which they would normally flee.

Thus, as artists, we must be able to mourn as well as rejoice, to shiver and worry and despair and break down as well as dance in the moonlight, make ecstatic love and eat ripe pears. To feel the feelings that are there, and then bring them through into form. *

My recent novel, The Revolution of Marina M., is set in a world of intense change, that of the Russian Revolution. It’s the story of a young poet trying to make art as she lives the common life of scarcity, fear, hunger, love and politics. In her radical poetry circle, arguments come up about the proper subject matter for poetry in radical times. I’m amazed how those arguments apply to our own torrential times as well.

Here’s the discussion of a poem my character Marina has written about women pumping water in the frozen courtyard of her apartment building (when the pipes have burst, as they did all over Petrograd during this period.)

A fellow poet, Zina, calls her poem counterrevolutionary, as it portrays this unhappy scene which seems to her a critique of the Bolshevik regime. But Marina feels its important to depict actual life “as we’re living it. Should I pretend it’s already paradise?”

“But you’re saying life is worse under the Bolsheviks.”

Marina says, “I want those women to be able to look into the mirror of this poem and recognize themselves... Not some sentimentalized notion of ‘the people.’”

“You should write about the landlords not fixing the water,” Zina said. “They’d still see themselves, but it would also make a statement.”

Oksana came to my rescue. “Not every poem has to be instructive to be revolutionary. To depict the life of common people in the contemporary context is itelf revolutionary. This is poetry, not advertising.”

Zina stamped her small black boot. “There are no sidelines. Poetry is part of the fight.”

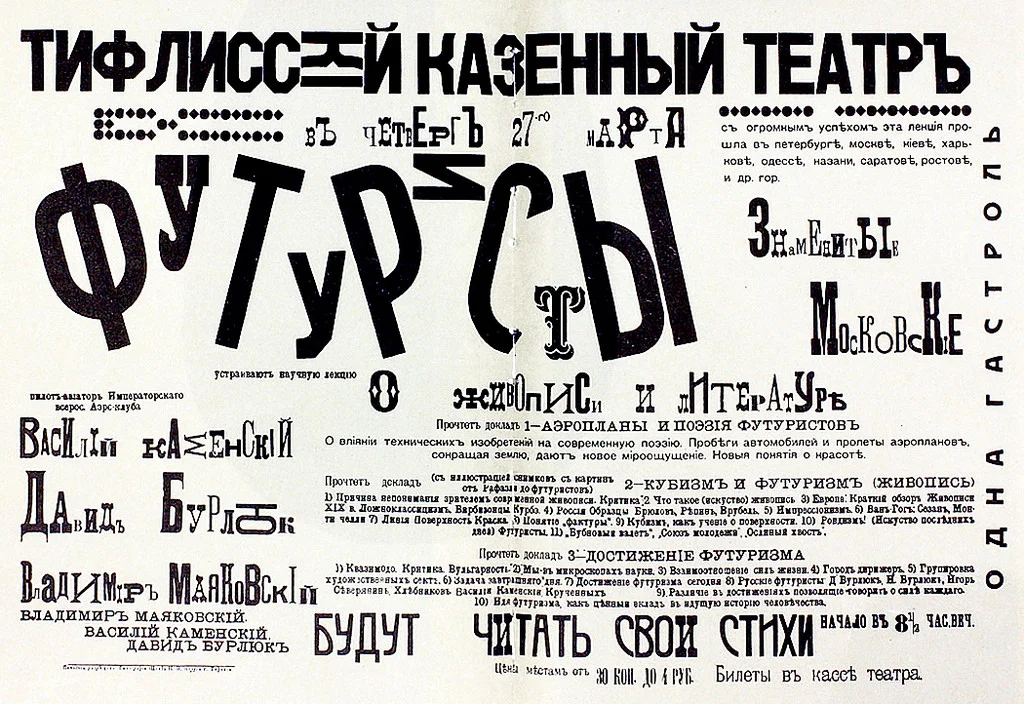

The leader of the group, Anton, a proponent of a radical Russian Formalism, called Futurism, interrupts this with a specifically literary point of view. “You’re all missing the point. The babas and their water aren’t the issue. It’s the form that’s the problem. You’re trying to make a Red Guardsman waltz in hobnailed boots... The revolution is in the lines or it isn’t a revolution.”

So here are three different responses to the problem of writing in revolutionary times. Does art have a responsibility to teach, to urge the reader in a political direction, to have a purpose outside that indirect or mirroring function in such dire times?

I think it’s a completely valid approach to write consciously political work. Faced with catastrophic events, artists create a lot of work of this kind. Some of it is very fine, when it aligns with how people live their lives and explores its characters in three dimensions, like Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. But much of it is ephemera, and doesn’t outlive its time--because it is heavy handed, populated with symbols instead of characters. Its authors hasn’t waited for the real meaning of the time to precipitate out, and we don’t read those works anymore.

Marina’s approach is to create a prose (or poetry) which mirrors the time, to simply depict things as honestly as she can, with a clear and accurate and understanding eye, on the everyday level. In this kind of work, the feeling of the time emerges from the portrayal of life. People recognize themselves and their experiences as true and real, and the author’s sympathies, rather than being overt, have a way of flavoring the art, but are concealed, often divided among the various characters.

Prof. Gill Plain (Literature of the 1940s: War, Postwar and ‘Peace’) quoted on Susan Sellar’s blog, describes traits of wartime lliterature in England:

“A fascination with the quotidian details of everyday life.... a lot of straightforward documentary work, people describing London in the Blitz, or what it was like to be in the army, or in a village full of evacuees, but you also find a fascination with the texture of everday life in more creative work – Elizabeth Bowen’s fiction, for example, is so richly textured, it seems to capture not just the sights of Blitzed London, but the sounds and the smells – even, in a very famous passage, the tangible presence of the newly dead; people ripped so unexpectedly from their lives that their ghosts still go about their daily business, invisible commuters, marked by their absence. She s acutely aware of how we build our lives, our identities, through things, and when those things are taken from us, we are cut adrift from memory and meaning. So, there is an astonishing attention to detail in the period, everything under threat is seen and written through new eyes.”

Prof. Plain also notes that postwar literature was marked by “preoccupations ... more internal, and a darker tone begins to surface. There’s an enormous amount of depressive writing in the latter part of the period, and a great deal of alcohol. Characters (and writers) drink themselves to death, there’s suicide and despair, futility – sometimes mitigated by a great deal of dark humour.” Books of this period include Nineteen Eighty Four, the Heart of the Matter and the Loved One.

Another response we can take is that of Anton and the Futurists--to create forms which in themselves reflect the texture of the times. You notice this in a number of highly fragmented works published recently, books which ‘feel’ right for our times, such as Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad ,and Amber Tamblyn’s Any Man, which show the speed and the colliding voices of the times, giving us a feel of the cacaophony and speed of the era, no time for a simple linear narrative. Jeff Jackson’s Destroy All Monsters has an insteresting counternarrative, and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights is shattered into bits—stories and non-fiction, the shards of which have to be reassembled in the reader’s mind. (The fact that some of these were written before all hell broke loose doesn’t alter the point of the nature of contemporary reality—Kandinsky’s seminal abstractions carry the violence of the First WorldWar a year before its outbreak, but everyone felt it coming.)

There’s naturally a lot of genre bending in our cultural moment, various forms coexisting in a single text—poetry and monologues, tweets and screenshots. After the Revolution, this kind of radical play was eventually crushed when Socialist Realism became the officially sanctioned style. Formal play is too difficult, too radical for a mass audience, which tends to be in fact pretty conservative aesthetically, but formalism, this play, is a truly revolutionary art.

So, to answer this question of how to write in a time of gale-force winds, there are as many answers as there are writers. You might like to write a more politically engaged fiction, specifically about the political events that are threatening us now. You might choose to use that extra clarity and emotion to write about the small things of daily life as we live it now, knowing this will also be political —because the emotions of the time ARE the times.

Or you might use this wild energy, the zeitgeist, this cacaphony-- to create new forms in which to express your story of the present.

Many writers are feeling guilty if what they’re writing isn’t au courant enough, political enough. That it isn’t the story of a refugee or a ICE agent or the family of a murdered black teenager or woman accusing a powerful judge of her rape. If it doesn’t address the political moment directly, they consider themselves irrelevant, outside the conversation.

But there are all kinds of writers, as there were in that poetry circle in Revolutionary Petrograd. Some writers naturally have a political story to tell. The social and political moment stirs them to action. Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath during the upheaval of the Great Depression. But he also wrote East of Eden,a far more personal work and also enormously meaningful. One is not necessarily better than the other. You write what you have in you to write. Your emotions and expereinces and the form in which you embody it is your art.

It’s the ‘should’ that gets problematic. When you write what you should write, the world isn’t getting the best of you. It gets the best of you when you write what you are compelled to write, and everything you’re feeling as a result of the times you’re living in will be part of that book. It can’t help but be part of it.

Think of a vineyard.

You plant this block of vines, you tend them, you prune, you do your best by them. But then there’s history—or call it weather. Does it rain enough and at the right time? Are the storms really awful one year? Does winter come and stay and stay and stay? Are there odd freezes and thaws? There is no way to keep that out of the wine. The grapes affected by those conditions will produce wine that reflects the conditions they were grown under.

And what’s really interesting is that sometimes, though the weather in a particular year is absolutely awful and output in that vineyard is low, the wine produced can be unusually good.

So there is no reason to feel bad if one’s work isn’t “political enough.” It will always be political, if the writer is an honest artist—because it will always be flavored by the place and time in which it was grown. Look at the books published in 1943, a time of terrific uncertainty. We get work that goes back in time, a serach for stability in one’s roots, such as A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. We get Herman Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game. We get Ministry of Fear—the meeting of political conspiracy and everydayness. We also get Brecht’s Gallileo and Good Woman and Szechuan. Take a look at the lists of books published in 1935—at the bottom of the Great Depression. We get They Shoot Horses Don’t They?--despair and poverty and the need for hope, but also Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge—a storyteller who normally didn’t go into the bigger issues, but the times came through.

So when you think you can’t work with all this madness going on, perhaps what you’ll get done in this heavy weather will be finer than what you would ordinarly be doing. The urgency of having something you need to say might push you further than you would have gone before.

I have had friends who were in the middle of books when this particular patch of bad weather broke out. They confided in me that they look at what they’ve been working on and it seems trivial, superficial, not worth doing, a part of something that doesn’t exist anymore. “It’s this novel about the wife having an affair, and who gives a damn if she does--the world is melting down! What do I do now?”

If you’re not connecting to it anymore, you can put it aside, and write what you’re connecting to now. You might come back to it later and find there’s lots worth saving.

You can keep working on it, but find a way to de-trivialize it, to make it matter more. Bring more artistry to it, more honesty, that ultra-vivid vision that was described in relation to Bowen—which dangerous times bring to the smallest thing. In case of this marital dalliance, you might think of The End of the Affairand how the times might color the action of your superficial book.

You might imagine a more radical form for it, reflecting the world’s meltdown.

However, it’s important to recognize that times of sudden, radical change are especially difficult for novelists. We’re slow, and novels take a long time to simmer. To say something deeply meaningful about the present, to even have a sense of what it means and where it’s going, takes time. These are enormous historic events. Poets usually are the quickest to respond to rapid social change—their art explores a single moment. It certainly was the case during the Russian Revolution. Perhaps this will be a golden age of poetry in America.

Short fiction is quicker, and then, poky and lumbering, bringing up the rear by a factor of ten, are the novels. You had few great novels of the Vietnam War until the 70s, into the 80s and beyond. It took time to process that experience. I would not expect big books about the Trump Era for years. But like that vineyard, everything written now will bear some taste of this unfortunate era--the despair, the panic, the depression and the fury. The resentment, the fear. I expect to see more fragmentation and more hybrid forms, given the speed of this change.

I also expect to see more of what Joyce Carol Oates called “commemorative” writing—fiction of an earlier time and place. In times of rapid change, many of us are strongly drawn to depict times and places meaninful in our own lives which are in danger of being forgotten. The past seems to offer a respite from the brutal sweep of the present, with its horror and cacaphony. But its fiction will always be flavored by the soil in which it was grown—it will bear the mark of these times.

Think of period films. While striving to be accurate and attempting to capture the feel and concerns of times past, period films always perfectly depict the styles and concerns of the time in which they were made. A ‘Fifties sword and sandal epic tells us so much more about the 1950s than it tells us about ancient Rome. “Spartacus” was a political film couched as a sword and sandal epic, shot during the McCarthy era in America. Its subject was a slave rebellion which succeeds because of the solidarity of the slaves. Books about the past will always be about the present and its issues and conflicts. Nothing is ever free of history.

So I would say, don’t worry about not being political enough. It’s plenty political, as long as you work with your real emotions—in fact, your book about those people’s affair might be more deeply political than a work scribbled off tomorrow about an orange furhrer and his lying entourage.

The important thing is not to allow these huge emotions just to lie there and fester inside you like an undigested meal—pull them through into stories and poems and plays, even into half-written novels. Write honestly and deeply, and let that extra sensitivity which living in these wild times has stirred up in you come through in whatever you decide to write.